Aubrey Samost-Williams is a resident in Anesthesia at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA. She spent the month of November at the Center for Medical Simulation (CMS) on an elective rotation. The goal of the rotation program is to expose residents to the potential and operational use of simulation for education, clinical training and research. Over the course of the month, residents develop simulation scenarios including patient records, plot, setup, debriefing notes, and references.

I had the privilege of spending the month of November at the Center for Medical Simulation learning the ins and outs of, well, simulation – how it’s run, how it’s taught, and how it’s debriefed.

My month kicked off with the Comprehensive Instructor Workshop where I learned the art of debriefing with good judgment, a skill I will certainly take away into every aspect of my life. I think if my husband hears one more advocacy inquiry from me, he might just sleep on the couch…

The next week it was time to buckle down and work on my resident project while practicing my new debriefing skills. The only problem was, I had no idea what my resident project would be. Spending that week watching learners of all levels and disciplines run through scenarios I was struck by how often they requested an ultrasound. In the clinical world today, it’s hard to find a facility with no access to an ultrasound. With the advent of cheaper and cheaper piezoelectric crystals, we now have access to ultrasounds literally in our pockets that can communicate with our phones. Ultrasound image acquisition and interpretation is being incorporated into a wide range of residency curriculums, including anesthesia, OB/GYN, and emergency medicine. And so I decided that my project would be to start incorporating ultrasound into the pre-existing simulation scenarios.

It turns out that ultrasound simulators are expensive – thousands of dollars per year kind of expensive. So I sought a cheaper alternative to bring point of care ultrasound (POCUS) to the simulation center; I wanted to build a low fidelity ultrasound simulator. There are two different skills at play in learning POCUS – image acquisition and image interpretation. Image acquisition was going to be hard to teach people with a low fidelity simulator, but image interpretation should be possible in this setting. Why can’t we bring real ultrasound clips to participants’ phones in a simulation, just like we can in the real world?

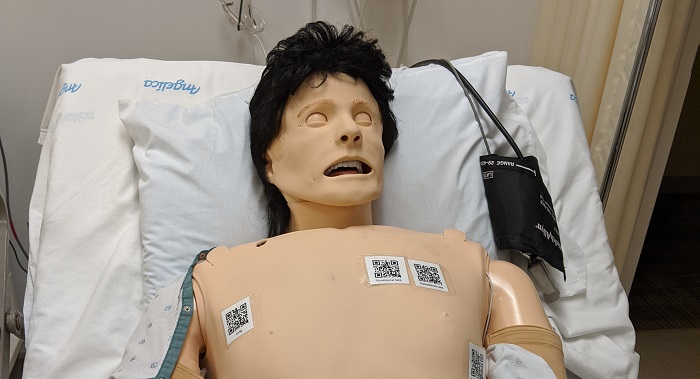

Enter QR codes. Have you ever walked by an advertising poster on the wall that says, “Scan here for more information” and offers a large square code? That’s a QR code. It can provide a link to a text file, phone contact, website, or as in this case, a video file. Try it yourself below! Simply open your phone’s camera and angle it to the QR code below. When a Dropbox link shows up, click on it to open the video. You should be directed to an echo image of an apical 4-chamber view of a normal heart.

I partnered with Dr. Rebecca Minehart, one of our anesthesia faculty members here at CMS to see if we could incorporate POCUS into one of our scenarios. We decided that a case of undifferentiated shock in the anesthesia course was a good place to start. I scoured the internet and our databases for deidentified POCUS images to support the diagnosis and built a set of QR codes to link to them. We then had a session of decorating our lovely simulation manikin with these QR codes in anatomically accurate locations. Doesn’t he look so technologically advanced?

We ran the first simulation with this new technology on the second to last day of my month at CMS. Much to my chagrin, that scenario took a different clinical turn and the participants never asked for POCUS images. Heartbreaking! But I still had one day left to see my project put into use. The following day during a resident and fellow anesthesia course we ran the same scenario. They took down my patient’s gown and immediately set someone to obtaining and reading the POCUS images. Throughout the debrief they discussed how helpful the images had been in guiding their care and narrowing their differential diagnosis. They were so happy with the realism of having the ability to obtain POCUS in a scenario where they would do so in the real clinical world. I felt validated and excited to see such a positive reaction to a project that I had been working on and worrying about all month.

We ran the first simulation with this new technology on the second to last day of my month at CMS. Much to my chagrin, that scenario took a different clinical turn and the participants never asked for POCUS images. Heartbreaking! But I still had one day left to see my project put into use. The following day during a resident and fellow anesthesia course we ran the same scenario. They took down my patient’s gown and immediately set someone to obtaining and reading the POCUS images. Throughout the debrief they discussed how helpful the images had been in guiding their care and narrowing their differential diagnosis. They were so happy with the realism of having the ability to obtain POCUS in a scenario where they would do so in the real clinical world. I felt validated and excited to see such a positive reaction to a project that I had been working on and worrying about all month.

Now that my dedicated time at CMS has come to a close I hope that my time working with them to bring ultrasound to the PACUs, ICUs, ORs, and labor and delivery rooms of the simulated Harvard Hospital has not ended. We have already started phase II of the POCUS project – upgrading from QR codes that are visible on the manikin’s chest to NFC (near field communication) tags that hide invisibly under the skin forcing participants to know where to look to obtain their POCUS views. All modern-day phones are equipped with NFC readers, which power such technology as Apple Pay and Google Pay. Hopefully, this will be ready to roll out shortly!

Stay tuned for phase III of the POCUS project – a phone app that will integrate the NFC tags with a wide range of POCUS clips covering the many clinical scenarios simulated every day here at Harvard Hospital at the Center for Medical Simulation.

-Aubrey Samost-Williams, MD